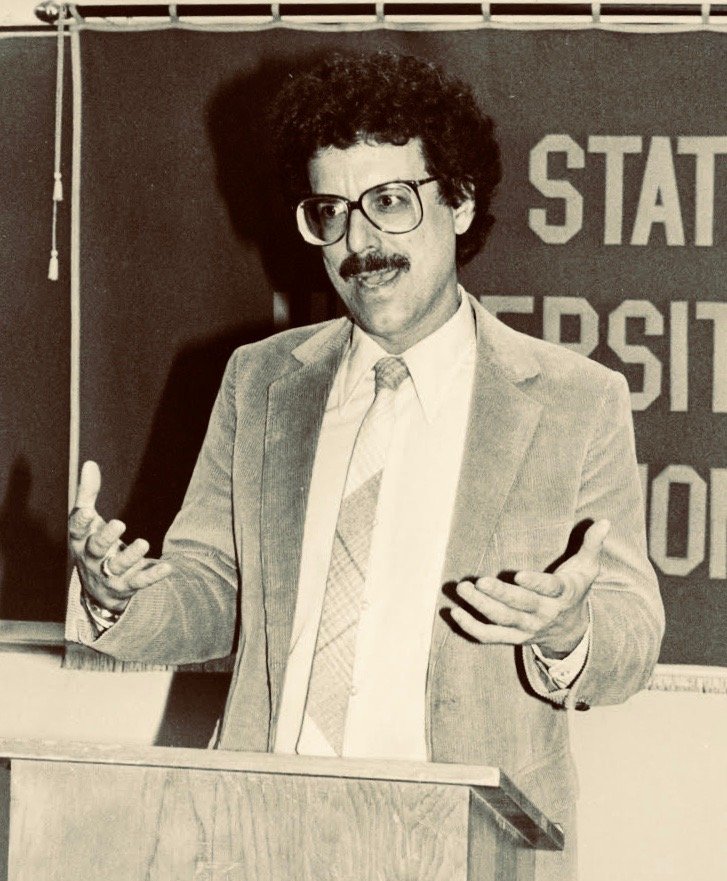

An Interview with David Citino Beloved Teacher and Poet

Introduction - Urban Spaghetti is proud to offer 43302.org the use of these Urban Spaghetti excerpts from the original interview with David Citino that took place in 1998 for Volume 1, Issue 1, of Urban Spaghetti. The issue was dedicated to David’s mother, Mildred, and to my mother, Evelyn Jean. With David’s words here I hope that his friends, family, and fans are given a smile with the memory. More importantly, I hope that people who did not know David come to know him and become inspired by this beautiful and brilliant man.

Urban Spaghetti – You are a professor of English and creative writing at The Ohio State University, on the board of trustees at Thurber House (a very active literary center for writers and readers), founder and past editor for The Cornfield Review, editor of The Journal, and involved with Ohio Writer magazine. Your poetry continues to be widely published in literary journals, magazines, and anthologies throughout the United States and the world. You have received numerous national and state fellowships and awards. This past summer you released your ninth full-length collection of poetry, AND you still find time to conduct writing workshops with visiting artists and serve as a judge in poetry competitions. You are an enormous success, David, yet you remain accessible, almost humble, really humble. How have you been able to retain your kinship with the common folk when you are far from ordinary?

David Citino – All those things that you’ve mentioned – by the way, it sounded almost as if my mother were going down that list, and I wish she were here to hear all that – but, what that means, I think, number one is that I’ve been around a long time, so you become something of a survivor. So you can say, “Well, I’ve done this, and I’ve done that, and I’ve done this.” But everything you mention is something for me that is a joy, is a passion to do. Poetry is my life. These are ways of professing that love for poetry, of DOING poetry in the real world.

I’m not and I’ve never been a kind of ivory tower, ivy-covered building poet. I think that poetry is a means of expression that is “of the people.” The highest form of praise I can get is when someone in a reading says to me, “You know, I hate poetry, I don’t like poetry, I’ve never read poetry, but, that poem you read about your father? I kind of like that.” Not that I’m out trying to make converts for poetry, although maybe I am at times, but poetry is a form of literature that is of and by and for the people. I guess the poet sees himself or herself as the “commonest” man or woman, the lowest common denominator.

Urban Spaghetti – In the foreword of your ninth book, The Book of Appassionata (The Ohio State University Press, 1998), you describe yourself as a “teacher-poet,” comparing similarities between the two professions. You pose the possibility that the poet…the teacher, may be “one and the same.” This is an interesting thought and one that suggests a certain amount of responsibility. Would you elaborate on how this might influence your writing and your teaching?

David Citino – There are different sides to me. I guess the two biggest or fattest sides are the poet and the teacher. I am a writer – every day working on my art and craft. I get to then walk into a classroom or a writing workshop and talk to people who are, too, attempting to write. I have a lot in common with them, and I tell them, and I mean this sincerely, that we’re all in this together. We’re all trying to take our art a little farther along.

It’s interesting that you ask me this question. I’m working right now on a book of prose that will be called Creating Poems, and it’s under contract with Oxford University Press. I’ve asked five other poets from around the country each to write a section of this book. I’ll write the sixth section. All of us are poet-teachers, so it will be an attempt I think, ultimately, to prove or disprove that contention I have that being a poet and being a teacher are either aspects of the same thing or maybe they ARE the same thing.

If I want to teach something, let’s say I teach a course here regularly on the Bible and English. Well, I have to go read the Bible, and then I have to read what other people have written about the Bible and think hard about it. And then I walk into the classroom having prepared things to say to the class. I want them to hear me, to be with me, to start their own process of learning. I want to write a poem on some topic you know – my father’s birth or his service in the Second World War. Then I need to do research and talk to him and learn more about it myself and then write it down. And in a sense, in the poem, by the act of the poem, teach me. And then teach the readers of that poem, if I’m lucky enough to have readers. The operation, “I’m going to teach you something” or “I’m going to recite a poem to you,” I think are similar in very important ways. One thing about teaching and poetry, it makes you realize how stupid you are. “I’m going to teach this room full of people this thing? My God! I don’t know anything about it. I better learn something about it.” And I think a poet, too, is constantly challenging his knowledge or presumptions or ideas.

Urban Spaghetti – There is some disagreement as to the definition of poetry…I can’t seem to find very many people who agree, really…

David Citino – You know, let me interrupt you, Cheryl. I just reviewed a book that’s going to be a textbook for some other press that another poet wrote. Her name is Wendy Bishop. She told this great story about when there were so many definitions and no one was happy with any of the definitions. She took a tape recorder and went to the faculty offices of the English department. She went from door to door, knocking on doors, and to everyone who came out she’d say, “Give me a definition of poetry.” Some of them wouldn’t; they’d run back in. It was so funny that she was in search, up and down the halls, just trying to get a definition. And that’s what it can be like. You can come up with a hundred, and none would really be satisfactory to everyone. To me, that’s probably because poetry is as big and as shapeless as we are, in a way. So poetry, a definition of poetry, has to include everything.

Urban Spaghetti – What are your hopes for the future of American poetry and for the small books and magazines that bring the poetry to the people?

David Citino – There’s a lot to be depressed about, I guess. Poetry! People don’t buy poetry. Everyone reads poetry. Few people buy it. Literary magazines and book publishers will tell you that you can’t get rich doing poetry. Poets will tell you that first, I suppose. That’s the bad news. There’s a kind of disconnect between poetry and “The Market,” which is so important to booksellers, and as we know, more and more booksellers are being purchased by bigger and bigger corporations that don’t know anything about books. But maybe that’s not all bad news. Maybe there needs to be some active growing segment of artists, writers, and readers who don’t give a damn about “the market” and “profit and loss” and “the bottom line,” and don’t feel that their art is some kind of commodity like Hostess cupcakes, that will be purchased and consumed and then more will be purchased and consumed. Poetry is doing just fine with volunteers, with the small presses, with people like yourselves who feel passionate about writing and want to learn more about it, want to further it, and advance it. I wish more poets and readers of poetry bought more poetry so we could have a little more of the other way, so we didn’t have to go to the Ohio Arts Council or the “whatever art council,” and beg for money or ask for grants that we could support a program.

One little thing that we do with our poetry series is everyone who submits a manuscript has to give us a check for twenty dollars, which seems a lot, and it is. But with that money, we publish the winning book and we support our literary magazine, The Journal, so that those people are, by submitting their manuscripts with their reading fee, supporting the endeavor of poetry, around here at least. So that is just one small example of what can be done.

Urban Spaghetti – I was in your class two summers ago, in the workshop, and you were trying to help me learn (laughter) along with the rest of the students, and you were saying, “Read it! Hear that poem!” Is there any difference between the poet and the poem…

David Citino – That’s an excellent question and to me, gets at the heart of what poetry is. We tend to think, many people tend to think, that the poem is the fattest anthology imaginable on a very thin page. That you are supposed to read silently, to yourself, and then maybe have an exam on it the next day and tell the teacher what it means. That’s not poetry.

In the beginning, in every language we have records of, in every language we know about, writing is a new adventure. Speaking comes first. Poetry always was spoken, oral, just as music was. It was not silent. The ancient people couldn’t even read silently. They didn’t know what that was. The few who could were considered weird. “Wow, you can read silently?”

Cicero (a great orator and writer of ancient Rome) wrote to a friend once and said, “I would have written to you sooner, but I had a sore throat.” Now you think about that. Writing was even speaking aloud, the words. I think a poem is incomplete until the poet says it.

Another thing I do in my classrooms, as you know, everybody reads everything out loud. You try to fill the room with the words of all the poets, those of the class, those from the textbook, the so-called greatest poets of all time.

Get those words out. Get them bouncing around the room. I tell the poets that part of their composition process should be speaking the poem out loud. You should say to someone, “Here, let me read this to you,” as well as, “Okay, you read this,” as well as, “I want you to hear this and tell me what you hear.” Our voice makes the poem complete. It also makes our responsibility even greater, to write EXACTLY what we want to say.

When I am talking to you now, I’m Italian so I use my hands, and I can raise my voice, and I can talk real fast, or I can talk slow and soft. I can jump around in my seat. None of that is in writing. When you see my poem, it’s just there…on the page. I’ve got to put on that page some of what I would say if I were there reading the poem aloud.

Maybe someday you will go to the library. You will go to the poetry section. You’ll open up the book and you’ll see the poet jump up and talk to you, maybe in a hologram kind of way. The difference between speaking and writing gets right to the heart of the way a poem works or doesn’t work.

For me it is, “Wow, you ought to write a poem about that.” I mean in our conversation, the three of us, who we’re talking about right now, we could be making little (notes), “I better write about this, I better write about that.”

I hear my students say, “I don’t have anything to write about. I’m from a small town. I’ve never been anywhere. My parents are boring. I’m boring. My dog’s boring. There’s just nothing to write about. I’ve not climbed any mountains…”

But any life is so complex and so filled with mystery and wonder. The problem is you don’t have enough TIME to write it all down. It’s only one lifetime and I’ve got to drive here and get gas and do that and go to work. Our heads are just filled with things to write about.

Urban Spaghetti – Over the classes that I’ve known you, over the years that I’ve known you, I know you are a great storyteller. Will you share with us something of your personal life? You are married and have children. I’ve read in your poems a lot about your mother. I’m very sad to hear that she died recently.

David Citino – She was a beautiful person. This past Christmas, one of my sisters gave us all The Collected Poems of Mother. So, she had been writing poems on birthdays and all kinds of events over the years.

My parents, Mother in particular, but both parents were the children of immigrants who came from Europe and were dirt poor, were peasants, laborers who believed passionately that the way out of that, or the way to better one’s life, was education and reading and writing. To them (it was) an almost magical thing that America gave the opportunity to have.

From the beginning, I was told and started to learn and to believe that education, reading, writing were the ways that I could make something of myself. In that family background, even though we had no money, I was encouraged to study and do extra things at school and to go to the best schools. In Cleveland, my parents sent me to a college prep school where they had to pay tuition. I had to work, and we just scraped away, saved enough money to pay my tuition for four years. That made a real difference in my life. I’ve gotten wonderful support from family; there’s no doubt about that.

Our oldest is finishing his dissertation in history and (is) trying to get a job teaching at a university. We have a son who’s just graduating from Miami University and is looking for a job. Actually, he just got a job, which is great.

But our real challenge…a teenage daughter! Oohhh, my Goodness! Never knew how difficult that was. She’s wonderful. Beautiful kid. She’s got two sides to her personality. She’s a volleyball player, so it’s team sport, ninth grade, down and dirty, scrapping, sweating. She’s also a cheerleader. So you can’t break your nails. Your hair has to be perfect. She’s this walking contradiction where those two things are going on in her head in beautiful ways.

Baseball has always been important to me. My real ambition [was] always to be the first baseman – left-handed first baseman – for the Cleveland Indians. I thought that would be the greatest thing. I still do.

I’ve written a great deal about sports. When I was a kid I was a real jock. I spent so much of my youth on fields or courts or somehow just in a game with other people. High school sports, very big thing to me, but even then, I was such an athlete or pretended to be, reading and writing were…I was still doing that. I was the sports editor of my high school newspaper in addition to being an athlete. I was proud of that. I still am.

Urban Spaghetti – Music?

David Citino – Oh certainly! In our house, somebody was always singing. It was a big family in a very small house and there was music everywhere. The radio was always on. Later, record players were always going, people were always singing along. I guess part of it is the stereotypical Italian family, a house full of opera singers. Music is something terribly important to me now and to my family and always.

Urban Spaghetti – Who are your heroes…your poetic influences?

David Citino – Well, actually, going back over everything we’ve said so far, so that would include family, life, and everyone I’ve met – grandparents and theirs (ancestors), my parents, my wife, my children, my colleagues, the fellow poets.

I tend to read a great deal. I’m published in a lot of magazines. That means I get copies, and I get to read what other poets are publishing at the same time. I have to say I learn from them constantly. Not that I find things to steal, but I see what they are doing and how they are trying to solve the problems that I’m trying to solve.

There are some specific poets that I turn to again and again. James Wright, whom I know we talked about in class, most recent class you took from me. Ohio poet – Martins Ferry, Ohio – Dirt poor – Ohio river town. Place was always terribly important to him. I’m a poet of my place; Ohio is a great influence – the places I’ve lived for any length of time. I’ve been in Ohio so that Cleveland and Athens and Marion and Columbus, Westerville – are places that have influenced me. So the place is an influence to me as well as all the poets I read and admire.

Another Ohio poet I read all the time is Mary Oliver, who’s no longer living in the state but lived here for years and is, I think, one of the finest poets writing today. I would call her a mystical poet. Although, rather than the kind of noisy, urban poetry I tend to write, her poems are about nature, wilderness.

Urban Spaghetti – In Broken Symmetry, the poem, “The Land of Atrophy,” describes your hesitation at telling your mother about the diagnosis of M.S. The poem is intimate, touching, and very tender. The next poem, “Prognosis,” is less accepting, more questioning, even frightening. The condition of your health must lay heavy on your mind. And if you’ll talk to us about it…

David Citino – Oh sure, I don’t mind doing that at all. I’ve had this…got my diagnosis about ten years ago. When you first do, two doctors walk in and two nurses and a social worker, and you think about “that’s that.” It’s like saying you are going to die in four months. I remember I had a very heavy heart after I got it, but I’ve reached a kind of accommodation with the disease. I know I’m not getting better, but the worst of it seems to be relatively gradual. If I’m lucky, I’ll be old before I get into a wheelchair, let’s say. I walk with a cane. See, it’s a kind of fancy one.

The State of Ohio calls me handicapped, so I get to park in the front of Kroger’s and things like that. I can conserve my strength then for other things. Maybe this desk shows I live a full life. I have a full-time job, and then some. I am able to work, and I think somehow work keeps me going. If I say, “Ah, not feeling well today. Can’t do that. Better stay home.” And (if) I just start listening to my body and my hands and my legs and my brain, that’s not good for me. I need to ignore what I supposedly have and work as hard as I can and do the things I care about. Talking about family before, wonderful support from wife and kids and friends and that helps a great deal, too.

Editor’s note. To preserve the rich and expressive spoken language of Dr. Citino, and to maintain the semantic environment, this interview has been informally edited.

Ladders

David Citino reads a poem about DNA he composed for Dr. Susan Fisher's Biology 101 class at the Ohio State University.